By: Nia Thomas

If you have ever had a conversation about prostitution and tried to question a man's 'right to buy', the following outcomes are likely to be familiar:

1: The subject reverts back to the choices (agency, if you're in academia) of the women working in prostitution.

2: You hear musings about prostitution 'the theory' – what it could be like in an ideal world if we work to improve it.

And, if you persist;

3: Grave warnings that challenging demand will result in endangering women by reinforcing stigma and driving prostitution underground.

That some men will want to use prostitutes is seen as inevitable. Discussion about it is off-limits: punters are invisible.

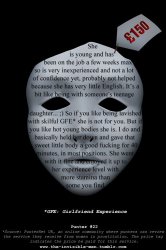

The Invisible Men is a political art project created to bring the words, attitudes and behaviours of punters into public focus, and to invite people to consider 'what do you think about his choice?' Launched on May 1 and running for one month, the project features a series of images of masks with price tags uploaded onto a Tumblr blog. The masks are overlaid with text, which are extracts from reviews punters have placed on the UK website PunterNet. The price on each tag indicates the amount the reviewer paid for his service.

The graphics represent the projection of demand onto women, but the blog offers no opportunity to deflect the question of choice away from the punter. His words are starkly presented and unavoidable.

I was introduced to PunterNet in 2006 after talking to a friend about the ‘choice’ argument. She sent me a link to the site, saying ‘I doubt these men have had to defend their choices in their lives’. That stayed with me. Reviews, known as ‘Field Reports’, take the following format: length of session, price paid, location, a description of the woman’s physical attributes and details of the ‘punt’. The review concludes by stating whether the woman is recommended. The reports paint a picture very different from the one promoted by advocates of the sex industry.

Conversations about the women’s choices never go into this kind of detail or mention the cold and distorted attitudes of punters who describe women like livestock. There is something disturbingly repetitive and casual about the way the punters discuss their actions. PunterNet is only one of many such sites: there are sites for other countries, for different cities, sites for men travelling overseas. As punters who use the internet to post reviews probably constitute a tiny percentage of punters worldwide, you begin to get a sense of how many men we're talking about and how widespread this is.

We can't talk about prostitution without looking at punters. They need to be visible.

The project has received very strong reactions. As expected, one criticism has been that particularly unpleasant reviews were selected to represent all punters. But such accounts are not rare and don't represent individual men. For example, Punter #2 comments that the woman he saw was Eastern European, exhausted, working long hours seven days a week. The reviewer will have been one of many men who saw exhausted women speaking broken English at the same establishment. The project has also prompted vows by some individuals to show the ‘other side’, that is, blogs with reviews by ‘nice’ punters and positive accounts by women working in prostitution. Considering that the PR machine of an industry worth billions already does this, I'm doubtful they will find a new angle. Positive response to the project has been overwhelming.

The New Statesman published a piece about it in the week it launched, and it has received support from a wide variety of groups tackling violence against women internationally, survivor-led organisations, exited women, and individuals. The most positive reaction to the project has been use of the blog as a resource to challenge demand and it has sparked interest in creating similar projects. One reaction that was doubtlessly well-intentioned was the creation of petitions calling for PunterNet to be shut down; however, such measures would do nothing to curb demand and would make the men invisible again.

By naming the source but not linking to the quote, the project encourages people to read through PunterNet and sites like it themselves. Not just to look for reviews indicating trafficking or violence (though there are many of these) but to see what demand looks like and develop an awareness of what punters do during their visits. I want people to read the casual way punters view and talk about women in prostitution, what the abbreviations that pepper their reviews mean (owo, cim, ro, gfe, pse, ee, etc), what they consider a good service to be, what they feel irritated or 'ripped off' by, how they interpret the women's responses, and also consider how they reflect on their own actions, character and appearance. Reviews express little interest in the factors we hinge our debates on, e.g. is she trafficked? addicted to drugs? in pain? exhausted? scared? repulsed by him? Where these indicators are present and too obvious to ignore, punters express irritation that she is being ‘unprofessional’, concern for their own welfare (demanding a refund, anxiety about getting in trouble with the police), or a suspicion after the booking that they have been conned.

The invisible men who have accumulated a decade's worth of reviews on PunterNet are not the darkest characters in society. They are ordinary men, professionals, husbands, and fathers who believe that sexual consent can be purchased. They are all the ones who make prostitution dangerous, they are the reason it exists, and they have to be accountable.

Nia Thomas is a London-based feminist and political artist